Mozart and Vocation.

A free man thinks of death least of all things, and

his wisdom is a meditation of life, not of death.–Spinoza, Ethics, 4.67.

In chapter six, “The Listenerʼs Perspective,” by far the best chapter of John Irvingʼs book Mozartʼs Piano Concertos, we are reminded that Mozart had a legendary memory and that his inspiration, his rhetorical inventio, came from a restless art of variation; in other words, improvisation and play; his play with the musical language he had learned and knew so well as to trascend it:

Both orators and composers need a store of techniques for making their raw materials work. Both have recourse to topics, which serve them as vehicles for the presentation of their ideas. In particular, an ability to ʻimproviseʼ upon topics demands an ability to apply techniques of variation, either in relation to the material itself or its setting, and it is this aspect of topicality in Mozartʼs piano concertos that will be pursued in the final section of this chapter, taking as a starting-point two recent thought-provoking essays by Kofi Agawu, who has argued for an approach to Mozartʼs music that takes account of his gift for ʻvariationʼ … understood … as a mode of discourse that may be imported into any formal musical situation, regardless of genre … What is highlighted in the ʻvariation modelʼ, proposed by Agawu is Mozartʼs gift for adapting his musical materials to novel situations, in ever new ways

Irving takes the finale of K. 467 (bars 239-313) as an example:

At bar 239, Mozart beings an episode in A minor – an unusual key in the tonal context of this movement – which concentrates substantially on the main theme of the finale. In the course of this episode he is, in effect, ʻvaryingʼ this theme, by means of internal changes to its length, intervallic shape and articulation profile, but also by means of changes to the environment in which it appears (including features such as tonality, harmonic profile, phraseology, texture and register). On one level, he is indulging in ʻplayʼ, asking himself the question, ʻWhat can I do with this theme?ʼ This section might therefore be regarded as a performative act, rather than simply a ʻtextʼ requiring analysis. Approaching it not from a preconceived philosophical position such as ʻgreatness is unityʼ, and valorising this section only insofar as its surface variety is reducible to a singularity (that is, the theme, or some yet more deeply embedded Urlinie of which it is in itself only a sign), but instead, as a celebration of the very act of play, we perhaps come closer to understanding it. Obviously, this episode has a ʻpurposeʼ within the design of the whole movement (for instance, as a point of tonal opposition, from which the aesthetic effect of the inevitable return of the tonic, C major, is to be measured). But seen as a ʻmomentʼ, isolated from such considerations, its live improvisational quality takes centre stage. This episode is a personification of Mozart the improviser, speaking directly, rather than in the ʻthird personʼ. The technical means through which he gives life to this element of ʻplayʼ is variation.

Irving concludes his greatest chapter like this:

Within this episode, Mozart demonstrates to the full his genius for ʻturning aroundʼ the content of his opening theme. It evolves by a process of almost continual transformation, reminding us that some of Mozartʼs contemporaries who criticised his compositions for indulging in excessive variety were perhaps not wide of the mark. No sooner have we grasped one feature of the process than its premises are altered again.

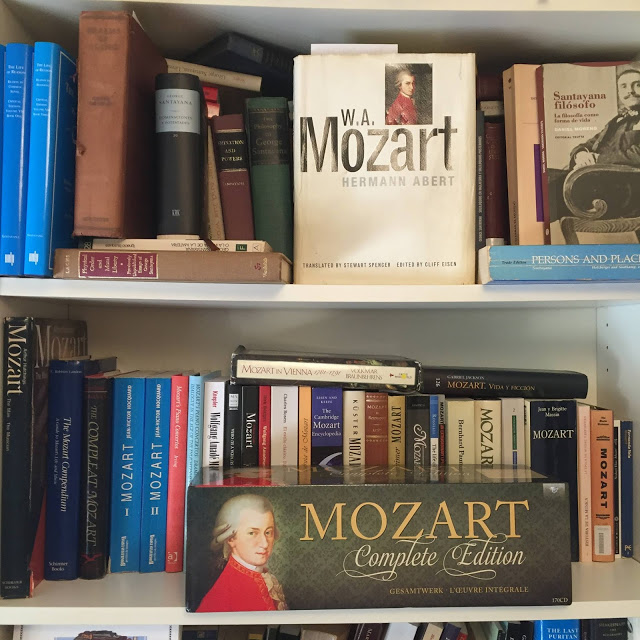

Which is what Hermann Abert criticises in Mozart in his great work; his tendency to avoid a profound development in his advanced ideas; his continual art of variation, an effect of Mozart the improviser; of Mozart at play. Piero Melograni writes (Mozart. A Biography):

Mozartʼs current popularity seems to me clearly greater than that of all the other great composers beloved by the public – Puccini, Verdi, Beethoven, Chopin, or Tchaikovsky, to mention a few.

The explanation must be, above all, in the nature of Mozartʼs music and in the extraordinary equilibrium he managed to create between tradition and innovation. Only artists capable of innovation can give a long life to their works. Innovation prompts tension, curiosity, and awe. It lights up their compositions. The works of conformists or academic composers are lifeless, precisely because they do not innovate. Their substance is bland and faded. Because they conform to fashion they may enjoy an ephemeral success but never a lasting affirmation. Mozartʼs compositions comply with the first rule for long survival: they surprise listeners and touch their emotions. If the composer wants to create that fecund emotion, he or she must be aware of innovating at the very moment of creation, avoiding exaggeration, however, since an exaggerated surprise is too facile and just as sterile as copying others. Thus one reason for the current triumph of Mozartʼs music is exactly what disturbed many listeners during his lifetime and what made more than one publisher hesitate to issue his works.

Yes, it is true what Picasso said, that “it takes a very long time to become young.” The example of Mozart, who never stopped playing with his art, is what makes his work immortal. That is why, too, it makes sense what we feel we hear in our hearts, according to Scott Burnham (Mozartʼs Grace): “We are ever aware of the pervasive availability of invention in Mozart’s music, which creates a broad effect of pervasive renewal and rejuvenation.” The genius was playing, which is what we do when listening to his music.

Comments

Post a Comment